6 Critical Elements to Determine Your Personal Minimums

22 November 2016 | Updated on February 05, 2024

I had my right wing cut low into the wind, with my left rudder pressed hard as I did my best to maintain centerline on a final approach back to Athens, Georgia (KAHN). The winds were high, and a good bit of it was crosswind. As I navigated the wind, I fought hard to keep from drifting off center while keeping my airspeed in check. I was confident yet relieved to feel that upwind main touch first, followed by the downwind main. No landing is perfect, but for the amount of wind I had to deal with, I was a satisfied pilot. It’s been years since then and I have more hours and wisdom under my belt, so would I fly that same approach in those winds today? Nope. I wouldn’t even be up flying with a wind straight down the runway in those winds. Why? Although I have more experience now than I did then, my personal minimums have gotten higher. That was during my instrument training. I was flying a couple times per week and had been for some time. I knew what I was able to handle and that approach at Athens was not below my personal minimums. Could I fly that approach in those winds today? Well yeah, probably. It might lack the polish, but I am capable of it.

Setting clearly defined, written down and regularly updated personal minimums is about knowing the difference in what you can do and what you should do. Let’s look at a few factors to consider when determining good personal minimums.

1. Recency of experience

I’m convinced that aviation skills must be made of some sort of metal, because they tend to get rusty fairly quickly.

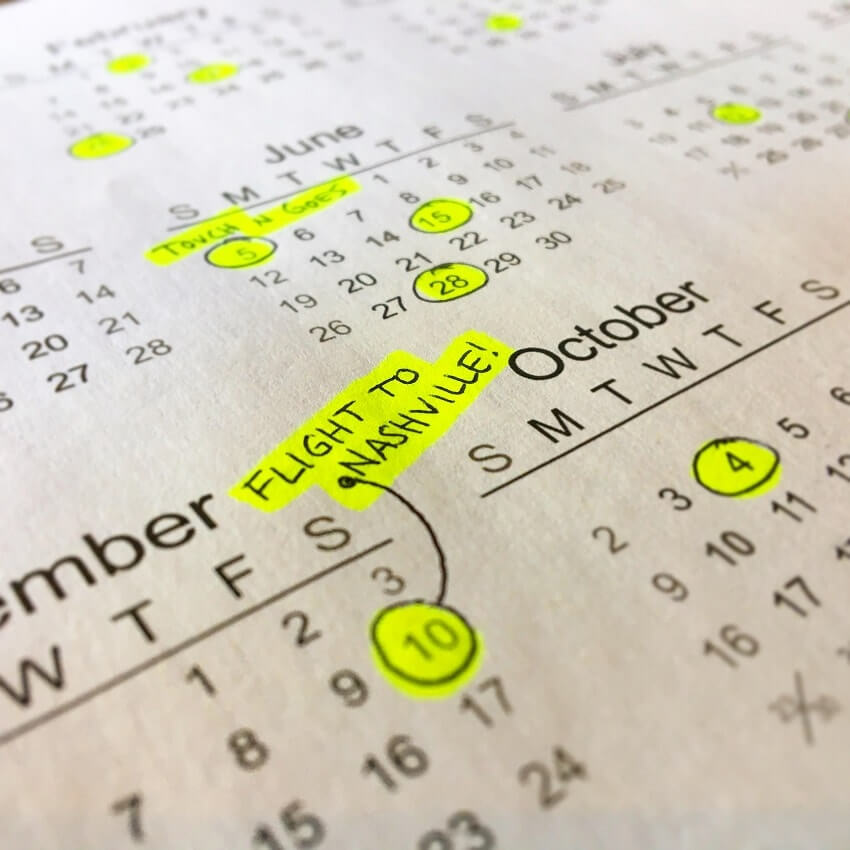

I took seven years away from flying, and returned as if I was learning it all over again. I hit the books and DVD’s like I knew nothing. I found that the knowledge and concepts came back fairly easily, but the application was like my initial training all over again. I was nervous, unconfident and didn’t have a groove. Currency requires that you fly only once every two years in a Biennial Flight Review to stay legal, and every 90 days to carry passengers, but what’s legal isn’t always what’s safe. How recently I fly impacts the hard set numbers I choose for the next few elements in this list.

2. Wind

Of the elements depicted on a METAR, I think wind is the sneakiest. You can open up Foreflight and look at a whole map full of green “VFR” dots (stations reporting VFR conditions)

and be deceived that it is a good flying day. Meanwhile, small tents at local tailgates are being blown away with the high winds. Obviously, I don’t just see a green dot and go flying, but having a top wind speed that you’ll fly in is important. Set a firm wind speed that is your limit, but keep in mind that how recently you’ve flown – especially in higher winds or crosswind landings – should influence that number. If it’s been a while, you might not be sharp enough to fly in the same winds as before with a reasonable margin for error built in.

but that doesn’t give any indication of the

high winds that might potentially ground your flight.

3. Cloud Height

For me, cloud height is one of the first and clearest cut factors to look at. If I’m looking to cruise at a certain altitude range, then I need the clouds to be above me. This usually means a fairly high ceiling as a VFR pilot who doesn’t support low scud running. Getting up above a scattered layer is something that many pilots will do, but anytime I plan on getting above anything, I’m looking towards the direction the weather is coming from for any ceilings that might be closing in, trapping me up in cloud land. If only we could land on the clouds like in the video games. Keep in mind, though, that the actual cloud height can (and will) vary from the forecast. Again, build yourself a reasonable margin for error so you aren’t surprised, or worse – trapped.

4. Visibility

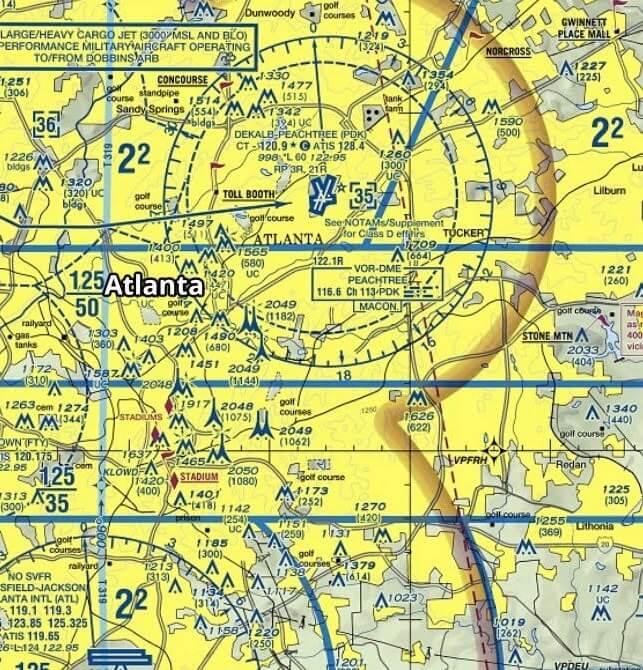

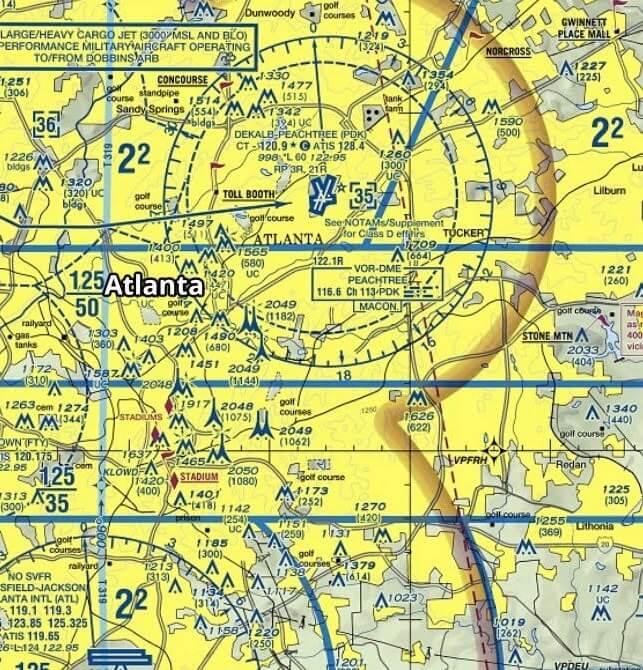

A picture says a thousand words, and in the world of Visual Flight Rules, visibility is critical. The photo in the caption below was taken on a flight between Atlanta, Georgia, and Chattanooga, Tennessee. The visibility was being reported as the full “greater than 6 miles,” but you can see how hazy it is. I don’t endeavor to get you a picture with only 1 mile of visibility, which is the legal minimum in class G airspace, because again, what’s legal is not always safe. This doesn’t mean that the laws are bad – many pilots can and do fly near the legal minimums and do so with confidence and precision. My personal minimums, however, are much higher than the legal minimums.

5. Complexity of Airspace

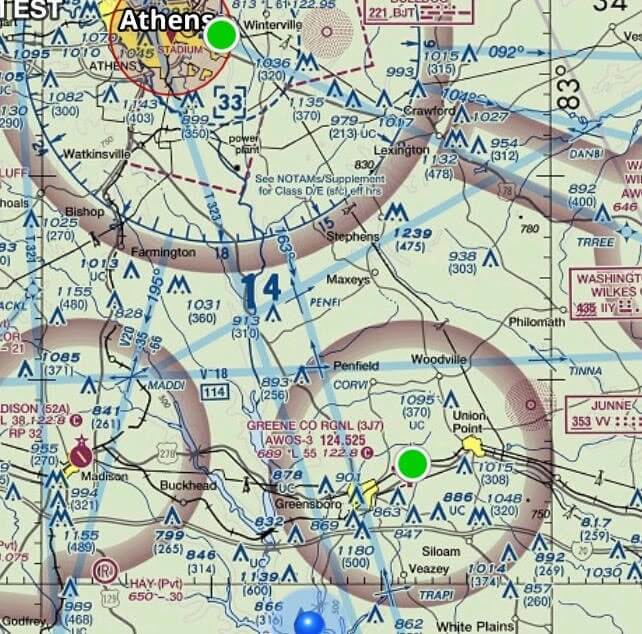

I’ve enjoyed the luxury of my training being done is fairly simple airspace. While I trained in Athens (KAHN), I was able to learn the Class D ropes of a towered operation but had plenty of open Class E around me. We would fly south to the “south practice area” for its nice open fields and farms underneath. I now have my home in the south practice area – it’s serene. Training and flying in more complex airspace inherently brings more to think about, more people to talk to, and more airplanes. Complex shouldn’t be confused with hard, however. It should just be approached with care in regards to your ability as a pilot. After my time away from flying, I chose my first few cross counties to nice, straightforward places with minimum complexity. After all, I was finding my groove again with my flow and thought processes, so while perfectly legal, a trip into the heart of Atlanta for a burger would not be a good choice for a rusty pilot. Say it with me – “what is legal is not always safe” when it comes to your personal minimums.

should yield different personal minimums than flying

once a month from a sleepy, rural airport.

6. Fuel

Running out of fuel just shouldn’t happen – yet it still does. A pilot flying out in my area recently ran out of fuel and had to land on the interstate. I don’t judge him for it because I know that it could happen to the best of us, but I learn from it and make sure I have my practices and personal minimums adjusted accordingly. I have disciplined routines like sticking the tanks at every stop – no matter what. My fuel is on my watch, not a gauge. And perhaps most importantly, I build a healthy margin around how low I allow the tanks to get. I got the low fuel light on a tank during a flight where I had planned and paid close attention to the fuel burn. I knew I was within legal limits and near the airport when it happened. Still, that feeling was enough to make sure I don’t get anywhere near it again. The legal minimum for fuel is 30 minutes past the point of intended landing. That’s not much room for error. I now have a hard set minimum fuel quantity to ensure that a diversion, go around, unforecast winds, or anything else won’t make me sweat fuel exhaustion.

One of the hazardous attitudes in flying is “macho.” What always comes to mind is a character from the movie Grease – some guy out to prove to his buddies that he can push the envelope. Flying isn’t about impressing people with your skills (unless you are an air show pilot with the appropriate personal minimums to impress). Good pilots make sure they have a large margin for error with their decisions. In a video game, or on the simulator, you can push the limits and test your minimums. Failure means you can reset it and try again. In the real world, however, there are no 1-UP mushrooms to give you another life. I wish I could give you a magic formula or quiz to determine your personal minimums, but by using some of these factors, you can make your own and feel good about them. Jot them down. Take them seriously. And don’t be tempted to push them just because you want to get there.

Be sure to visit Clayviation.com and subscribe for weekly content delivered to your inbox. Also find us on Facebook and Instagram @Clayviation.